I find it interesting how perspectives on 9/11 differ according to where you were, and not who you were, when it transpired. New Yorkers relate to it quite differently than Nebraskans. They have the acute sense of human loss and sadness because they saw the towers everyday, because they have relatives who worked there, because they are in a position to give blood that could save lives, because it was their backyards. Nebraskans, on the other hand, have no such immediate and visceral connection, so their response is to immediately symbolize - put in a historical, political context. Nebraskans will jump to military action, put up posters, make little flags to be worn patriotically, argue about jingoism, judge all parties involved - but all of these reactions are distant and indirect and somehow much less sincere. It makes me think that people who made profits out of 9/11 were probably not New Yorkers.

Of course, Nebraskans can't think the way New Yorkers do about September 11th. Our only connection is a national one - so our response is nationalist (or anti-nationalist). All we know to do is rationalize it to something we can write an essay about - we don't think about the immediate casualties of people who died - those of us who claim to consider this are unconsciously lying. How can we think of the people who died? We're too disconnected from that - disconnected because we see it through a cathode ray box, through heavily-filtered news media. Everything human about the experience has been drowned out by the time it reaches our senses.

And though the new 9/11 movies coming out are going to try to put us where we could not be by recreating the terror and horror and mass panic and confusion of the day, it will not be successful, because the moment has passed, and the replacement moment is artificial. They should take something out of "Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction". Art. Mechanical. Reproduced. For art it may be alright, but for catastrophes?

3.29.2006

3.28.2006

A Place Called Chiapas

Watched this movie in Comparative Politics, to go along with our lecture on social movements. I was expecting an old, faded documentary, maybe something they would show on PBS that my mother and I might watch if we didn't find something more entertaining, like a good Poirot or Midsummer Murders. I did not expect the level of personal, on-the-ground scope that "A Place Called Chiapas" provided. The crew was Canadian, led by a young and brazen Nettie Wild (can anyone say Nike Delmont?) with a Mexican translator and they ventured into the village of La Realidad, where the Mexican military's authority, post-1994 ceasefire, unofficially ends and the authority of the Zapatistas (which they insist is really the authority of the 25 million indigenous people speaking a variety of Mayan tongues) begins. They also visited a family of big ranchers whose ranches were seized by the Zapatistas during the 1993-4 uprising and "destroyed" according to the ranchers, "converted into homes and space for a school, church, and sports field" according to the Zapatista-supporters who now live in the multi-room houses. The crew also went to the north, to a village with an unpronounceable name and the mountains nearby, where Zapatista supporters had been driven to by a paramilitary called Peace and Justice, to the detriment of their children and elderly.

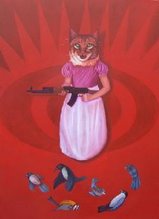

A family of guerillas

A family of guerillasThat struggle of the 2,000 refugees to return from the muddy mountains to their houses was the heart of the film. The paramilitary interviewed in the village before their attempt claimed that the refugees, by virtue of being Zapatista supporters, were armed and dangerous, and that the Zapatistas had murdered dozens of their comrades in the Peace and Justice PM - that they were not the enemy. It was the similar tone taken by the family of ranchers. They dodged questions of racism and exploitation to drum home the destruction of their ranchhouse, the stealing of their cattle, and the elusiveness of Marcos, whom they see as a masked terrorist.

Subcomandante Marcos was of course the other intoxicating fixture of the movie. I suppose he's titled himself subcommander because he claims to obey the indigenous people, but by all rights he is clearly the leader of the movement. After peace talks break down (the documentary makes it seem as though Marcos breaks off peace talks over the internet after Nettie Wild brings up the issue of the unprotected, neglected refugee-supporters in the North, but there may be more to it than that), the Zapatistas decide to send a delegate to Mexico City to the indigenous people's convention. But the identity of this delegate changes at the last minute from Marcos to subcomandante Ramona, an Indian woman who speaks no Spanish and is cancer-ridden, frail and poor, an emblem of the weak humanity that the Zapatistas may see as a more sympathetic image than the gun-toting, charismatic, pseudo-terrorist Marcos. He is clearly just as affected with charismatic authority as Mao and Roosevelt, joking with reporters and then becoming stern and philosophical with them, signing leaflets for children, posing for Marie Claire magazine, always in his black ski cap, the shots tailored to show his young and deep black eyes.

Subcomandante Marcos

Subcomandante MarcosHe clearly evokes memories, especially for this politically conscientious college crowd, of Che. I admit I belong to the group "Students Against Silkscreen Che", because I'm skeptical of buying shirts from capitalists to demonstrate your support of a communist, because I'm skeptical of demonstrating blind support for any one person, save perhaps those few gems that are clearly in the highest realm of morality like Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi. But that doesn't mean my colleagues at Barnard/Columbia don't wear their Che shirts. And Marcos fits their revolutionary daydream model of a hero as well. Some in the room were clearly slanted toward Marcos and the Zapatistas. This is natural. I think many people, even moderates among us, are, because the Zapatistas, though they attacked cities in Chiapas like San Cristobal, are hardly al-Qaeda. But I heard indignant laughter and scoffing when the ranchers and the paramilitary spoke. I didn't really laugh or scoff. There is humanity in their eyes too. They have valuable perspective. It's how I know I'm unzealotizing my liberalism.

Like the bishop who tries to mediate peace talks even now, I wish peace talks worked. But they require both sides to adhere to certain rules, and the paramilitaries clearly are overstepping their boundaries in northern Chiapas. This is a Mexican state problem - they need to eliminate those paramilitaries, in my opinion. They serve no purpose other than as slippery vehicles of state-sponsored terrorism. The only reason the bloodshed has not been worse is the presence and attention of the international media. Mexico fell into this problem because they wanted to become part of the First World. They're not going to ruin their welcome by slaughtering the remaining Mayan population as long as the cameras are watching. As Nettie Wild details, as soon as she put the camera down in that unpronounceable northern village, the paramilitary attacked her crew and the refugees with rocks, hitting her translator, forcing the refugees back out of the village and into the periphery. But when the cameras aren't watching? And worse, I think, the Chase Manhattan Bank memo: advising the Mexican government to eliminate the Zapatistas.

I'm afraid Mexico so desperately wants (and in the long-run, I suppose, needs) to jumpstart its economy that it will do whatever foreign investors and governments advise. If those in the industrialized world lose their consciences in their desire to reap the benefits of a trade arrangement with Mexico, and we start not to care about the carnage and civil war, that's when Chiapas will fall into an abyss. We need to maintain a conscientious eye, looking out for the civilians out there. Our disapproval of state-sponsored terrorism is sometimes I think all that keeps them alive.

Read the interview with Nettie Wild

3.27.2006

Lights Will Guide You Home

I lost my concert-virginity last night. To Coldplay. And I must say that I am very glad I waited. Midway through the performance I realized why I love this band so much - why I dedicated the title of this blog to them (from "Don't Panic"): because they make me believe that there is good in the world, and they make me believe in that good.

I was coming off a brunch conversation with my roommate Kim about soulmates and love and whether they exist. Over cheese-eggs and potatoes I was willing to acquiesce that the idea of a "soulmate" - or an OTP (One True Pairing) in fanfiction speak - may be a little far-fetched, even for fiction. But I was not willing to acquiesce love. And after seeing Coldplay in concert at Long Island's Nassau Coliseum, I'm even more unwilling to surrender it, this final outpost where we survivors believe in that elusive good.

Chris Martin makes me happy. His white sneakers and black get-up, the wardrobe change he did in the middle to a different black shirt for the song "Kingdom Come" that they wrote and dedicated to Johnny Cash (especially poignant considering the three of us who went, Amanda and Lucia and I, had just seen "Walk the Line" over spring break), that he's married to Gwyneth Paltrow and has a daughter named Apple, that he fell on the yellow ball of glitter that dropped from the ceiling for the performance of "Yellow", making glitter explode over the stage, that he ran wildly and frenetically to the back of the coliseum to dive into the crowd of people in those nosebleed section, that he and a guitarist fell on the stage and played lazy, dreamy music under twirling blue spotlights, that he went up and put his palm on the screen during my favorite song's favorite lyrics: "You're part of the human race/ All of the stars in the outer space/ Part of a system, a plan" from "White Shadows".

We restrained ourselves throughout most of the performance, sitting on the upturned seats of our chairs instead of dancing to accommodate the woman behind us, but during the last song, "Fix You", we had to get up and dance, and it just didn't even matter anymore. Everyone was up. As Lucia commented, it's the only time that she can dance in front of so many people and not care. I couldn't even be self-conscious at that point. I was screaming the lyrics to "Fix You" along with the rest of the audience: "Lights will guide you home/ and ignite your bones/ and I will try to fix you" (an effort that was perfectly understandable and perfectly pitched, might I add, for the size of the crowd), I was letting my head rock if it wanted, my hands flail however they wanted.

I sang along and could barely hear myself, but that was wonderful because I did feel as if I was part of the human race, part of a system, a plan - the plan might have been called any one of twenty-some songs but that was just its ever-changing title. The plan itself was far more vast.

That sense of community, of kinship, not only with the band that's obviously rocking its heart out for you and for themselves and for life itself on the stage amid a flurry of flying colors, but with all the people there with you who are just as passionate as you, just as fervent, swaying to the music like you are, clapping in time with you, sitting with their hands clasped excitedly because this moment is as religious for them, though perhaps in slightly different ways, as it is for you. And it just increases the faith you have in the world, when you feel this - because it's not just this four-person band that is manifesting beauty and bliss, but all of you are. All humans are, as we I suspect believe deep down inside, capable of manifesting that, of living and breathing that beauty and bliss.

Coldplay's songs, after all, are not about being rich rockstars. They're for anyone to relate to, and everyone can relate to them. They're songs about finding your place in the world, finding out if you're "part of the cure/ or [...] part of the disease", self-actualization. Songs about being human on this flawed Earth. And the grandeur and wonder of these songs makes you believe that life here can be grand and wonderful, if we just make it so.

As the bittersweet, beautiful song that my Spanish highschool teacher attributed to me, "Don't Panic", goes: "We live in a beautiful world/ Yeah we do, yeah we do".

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)