Watched this movie in Comparative Politics, to go along with our lecture on social movements. I was expecting an old, faded documentary, maybe something they would show on PBS that my mother and I might watch if we didn't find something more entertaining, like a good Poirot or Midsummer Murders. I did not expect the level of personal, on-the-ground scope that "A Place Called Chiapas" provided. The crew was Canadian, led by a young and brazen Nettie Wild (can anyone say Nike Delmont?) with a Mexican translator and they ventured into the village of La Realidad, where the Mexican military's authority, post-1994 ceasefire, unofficially ends and the authority of the Zapatistas (which they insist is really the authority of the 25 million indigenous people speaking a variety of Mayan tongues) begins. They also visited a family of big ranchers whose ranches were seized by the Zapatistas during the 1993-4 uprising and "destroyed" according to the ranchers, "converted into homes and space for a school, church, and sports field" according to the Zapatista-supporters who now live in the multi-room houses. The crew also went to the north, to a village with an unpronounceable name and the mountains nearby, where Zapatista supporters had been driven to by a paramilitary called Peace and Justice, to the detriment of their children and elderly.

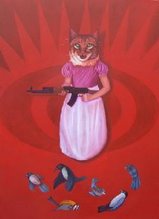

A family of guerillas

A family of guerillasThat struggle of the 2,000 refugees to return from the muddy mountains to their houses was the heart of the film. The paramilitary interviewed in the village before their attempt claimed that the refugees, by virtue of being Zapatista supporters, were armed and dangerous, and that the Zapatistas had murdered dozens of their comrades in the Peace and Justice PM - that they were not the enemy. It was the similar tone taken by the family of ranchers. They dodged questions of racism and exploitation to drum home the destruction of their ranchhouse, the stealing of their cattle, and the elusiveness of Marcos, whom they see as a masked terrorist.

Subcomandante Marcos was of course the other intoxicating fixture of the movie. I suppose he's titled himself subcommander because he claims to obey the indigenous people, but by all rights he is clearly the leader of the movement. After peace talks break down (the documentary makes it seem as though Marcos breaks off peace talks over the internet after Nettie Wild brings up the issue of the unprotected, neglected refugee-supporters in the North, but there may be more to it than that), the Zapatistas decide to send a delegate to Mexico City to the indigenous people's convention. But the identity of this delegate changes at the last minute from Marcos to subcomandante Ramona, an Indian woman who speaks no Spanish and is cancer-ridden, frail and poor, an emblem of the weak humanity that the Zapatistas may see as a more sympathetic image than the gun-toting, charismatic, pseudo-terrorist Marcos. He is clearly just as affected with charismatic authority as Mao and Roosevelt, joking with reporters and then becoming stern and philosophical with them, signing leaflets for children, posing for Marie Claire magazine, always in his black ski cap, the shots tailored to show his young and deep black eyes.

Subcomandante Marcos

Subcomandante MarcosHe clearly evokes memories, especially for this politically conscientious college crowd, of Che. I admit I belong to the group "Students Against Silkscreen Che", because I'm skeptical of buying shirts from capitalists to demonstrate your support of a communist, because I'm skeptical of demonstrating blind support for any one person, save perhaps those few gems that are clearly in the highest realm of morality like Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi. But that doesn't mean my colleagues at Barnard/Columbia don't wear their Che shirts. And Marcos fits their revolutionary daydream model of a hero as well. Some in the room were clearly slanted toward Marcos and the Zapatistas. This is natural. I think many people, even moderates among us, are, because the Zapatistas, though they attacked cities in Chiapas like San Cristobal, are hardly al-Qaeda. But I heard indignant laughter and scoffing when the ranchers and the paramilitary spoke. I didn't really laugh or scoff. There is humanity in their eyes too. They have valuable perspective. It's how I know I'm unzealotizing my liberalism.

Like the bishop who tries to mediate peace talks even now, I wish peace talks worked. But they require both sides to adhere to certain rules, and the paramilitaries clearly are overstepping their boundaries in northern Chiapas. This is a Mexican state problem - they need to eliminate those paramilitaries, in my opinion. They serve no purpose other than as slippery vehicles of state-sponsored terrorism. The only reason the bloodshed has not been worse is the presence and attention of the international media. Mexico fell into this problem because they wanted to become part of the First World. They're not going to ruin their welcome by slaughtering the remaining Mayan population as long as the cameras are watching. As Nettie Wild details, as soon as she put the camera down in that unpronounceable northern village, the paramilitary attacked her crew and the refugees with rocks, hitting her translator, forcing the refugees back out of the village and into the periphery. But when the cameras aren't watching? And worse, I think, the Chase Manhattan Bank memo: advising the Mexican government to eliminate the Zapatistas.

I'm afraid Mexico so desperately wants (and in the long-run, I suppose, needs) to jumpstart its economy that it will do whatever foreign investors and governments advise. If those in the industrialized world lose their consciences in their desire to reap the benefits of a trade arrangement with Mexico, and we start not to care about the carnage and civil war, that's when Chiapas will fall into an abyss. We need to maintain a conscientious eye, looking out for the civilians out there. Our disapproval of state-sponsored terrorism is sometimes I think all that keeps them alive.

Read the interview with Nettie Wild