In an episode of Law & Order the NYPD detectives meet an uncooperative FBI, and Lenny Briscoe says afterwards, in traditional New York sarcasm, "Join the FBI. Learn to pass the buck." But it's not just the FBI, Lenny.

Because Amanda has absurd connections and a friendly family, she got four all-day passes for this first weekend of the TriBeCa ("not Tribeca," Mir would urge) Film Festival. That means the only money we have to spend is subway fare. While we did get complimentary mini-Zagat's at each showing equipping us with info about the best (read: priced moderately or above) shopping, food, hotels, and attractions in the neighborhoods that surrounded the TriBeCa theaters, which really sprawl far and with random array across lower Manhattan, not at all staying loyal to TriBeCa, it did feel like a uniquely New York crowd. Even if they weren't from New York they were willing to put on the facade of New York City. Maybe I haven't been here long enough, but I feel like this city, for a huge part, is really just a game of masks and costumes and attitudes. People say you can feel New York in your soul. I think you can feel the desire to be New York, but what is New York? So it wasn't a uniquely New York crowd - it was just a uniquely New York-esque crowd. And I was proud when filling out the cheap little questionnaire/marketing gimmick in the first pages of the Zagat's to say that my last purchase was a Metrocard. Can you get more New York than that? New York as an adjective. New York as a description. It is not a place, and it is not a state of being.

The first film I saw was Brasilia 18%, by apparently one of the world's most prominent filmmakers (but of course, being an American, I had no idea who he was). He and some of his stars stepped up at the front of the screen before the movie started to modest applause. I picked out the movie because it was supposed to be about political corruption and crime in Brasilia, Brazil, and I was tired of all the "quirky romances" that make up most of TriBeCa's offerings. Of course, there was a weird spattering of romance in Brasilia 18% too - all of it very surreal and hallucinatory. But it did successfully discuss corruption, in a hugely over-the-top and tongue-in-cheek manner. At one point a Senator Romero says something along the lines of, "You brought an honest man in here? Who says I wanted honesty?" Everyone from the politicians to their drivers discuss pay-offs with calm, matter-of-fact blase. They don't see anything wrong with their actions. They see it as the way politics is done. When one politician, I believe from the opposition party, has to hold a press conference in response to charges of corruption, he is spoonfed his outrage and indignation at the accusation by a senior adviser.

The "honest man" is Dr. Bilac, a medical examiner from L.A. who was brought in to ID a corpse at the morgue as that of Eugenia Camara, a missing young woman who at first seems to be an actress, but then is realized to be an economist working on the budget with Senator Romero. At first her story is a successful product of a meritocratic civil service - she placed highest on the ministry exam, her mother explains, and she went straight to work, as her mind was obviously capable of doing. But then there's a "porn video" that's really a taped gang rape, there's the accusations that she was involved in indiscretions with various Congressmen, there's the budget that appears to have been altered - "fixed" - to help Senator Romero's causes.

Everybody in the city (perhaps the country) - Senator Romero and co., Senator Romero's licentious daughter Georgesand, the kingpin journalists, the unbelievably crooked cops - wants Dr. Bilac to say the body is Eugenia's, so they can nail her boyfriend on the murder and dispel further scandalization of the powerful. They can spare her moviemaker boyfriend (I think this was a bit of a self-deprecating move on the director's part, to make the wretched, junkie boyfriend a moviemaker - at one point Georgesand says, "Another stupid Brazilian movie, who cares?"), but not the whole fucking Congress. As the state medical examiner (and Dr. Bilac's brother-in-law) Martins says, "If hearings worked, half of Congress would be in jail." But Dr. Bilac is convinced that it's not Eugenia. He gets a phonecall from her, in fact. Hallucinations about seeing her in the shower tempered with hallucinations of his dead wife aside, it does seem highly possible - though hugely unconfirmed by the movie's inconclusive ending - that Eugenia is just in hiding, humiliated by the surfacing of the video of her being raped and probably intimidated into silence by the cops that are really the Congressmen's drivers and thugs. As he keeps refusing to sign the report saying it's her body, the establishment gives up trying to woo him with dinners and lunches and Georgesand's affections, and moves on to full-on threats.

And Dr. Bilac gives in to save his sister and brother-in-law's reputations, as well as to save the life of a young prostitute. He gives the strand of hair Eugenia's mother gave him to Martins for safekeeping - "so we know the truth" - and then signs the report against his conscience. He then is escorted back to the United States. It's sad, but I don't think the movie could have ended any other way. Realistically, Dr. Bilac wasn't going to sacrifice everyone just to hoist his own moral pillar. Nor was he going to get a gun and battle the thugs to death and/or victory. Realistically, he was going to give in. Everybody has a price.

That theme went on as the night did. The second film was a documentary called Cocaine Cowboys, by some young charismatic, edgy director with a cult following that applauded him whenever he made an appearance either on screen (his name) or in person (in an ironically Miami Vice white suit). It was tremendously hard to get to that theater, involving going over a very sketchy bridge that crossed one of the few highways I have seen in Manhattan, West Broadway. But the movie was worth it. I was there with Kim, who hates explosions and gunfire (which was of course what the film opened with... but most of the gore subdued after that, limited to photos of corpses with dozens of bullet holes every so often).

The documentary concerns Miami in the late 70s, early 80s, when most of its income was from cocaine, when the borders were completely unpatrolled, when everyone, from the clubbers to the lawyers to the doctors, are lining up cocaine on glass tables. The movie's main interviewees were Jon (the New Yorker) and Mickey (the redneck) - they were not the cowboys, they were just the transporters. And they made unspeakable amounts of money coming up with an ingenious (really... it's kind of pathetic that as a species we can spend so much brain power on how to smuggle drugs into a country and we can't devote the same mental prowess to things like, you know, AIDS prevention) method of delivery involving airdrops of bags of cocaine, hollowed out boats, planes that landed in privately built and owned airstrips and held in hangars disguised as barns, their own towing company that could "tow" vehicles carrying cocaine and then get off scot-free if pulled aside because, hey, they're just the tow truck, going south instead of north to throw off the authorities, paying everybody on the block to keep watch for cops.

While the two (who were at the movie, much to our alarm) - especially Mickey - would say that they weren't really hurting anybody, that the violence was what fucked up the whole business, and that resulted when the Colombians and Cubans started fighting each other on account of earning the most money selling cocaine, I'm not so sure if I buy that. It's a core question of the drug debate - do drugs, in and of themselves, violence from drug wars not included, actually hurt anyone? After all, it brought in millions for Miami. Half the skyline, so most of the film's interviewees admit, is built on drug money. It turned Miami into an actual city, not a place to die for retirees.

The first response to the question is the overdoses - two deaths a week from overdosing on cocaine is a pathetic waste of human life - and the second response is whether the violence that ensues isn't inevitable. Do drugs like cocaine ever let a city swimming in them rest in peace? Guns seem to follow naturally. Look at Medellin, Colombia, where it all started - probably up there in the most dangerous places of the world. I don't think that's because "drugs make people do crazy things", but because the money. That's what it all came down to, the film's interviewees pressed - it's the money, not the cocaine, that kept them in the business. One audience member asked, "Why didn't you just call it quits while you were ahead?" to which Jon responded, "Why would we? We could make so much more." And the audience member shouted, "You had millions of dollars!" But if you can have even more millions... that's the thing about money. I know that even as a poor college student surveying my bank account. You set a goal to yourself - I'm going to come home with X amount of money - but if you surpass that goal, you're not going to stop working, you're not going to stop saving. You're going to keep on raking it in. You always want more. It's called greed, it's called humanity.

So pretty soon all of Miami is drowning in their cocaine and in the drug money. The politicians weren't so hot on the drug, but the money they would be willing to accept. A doctor said that at one point you could take a random bill out of your wallet and it would have cocaine on it. I'm not surprised since there were entire banks devoted to managing the drug money - "cocaine banks", of course. Jon was a regular donor and welcomed guest of the Republican Party's inner circles (Strom Thurmond was a name frequently thrown around). The police force, woefully understaffed, tried to recruit new members and to do so had to reduce their requirements to, as a reporter said, "if you are not currently under the influence of drugs, you're hired". Of course this means the police is crawling with cocaine dealers too. Even the D.A., one of the supposed "good guys" of the movie, was revealed during the end credits to be tried on obstruction of justice. The only "straight" people in the movie turned out to be a couple veteran cops who obviously were so filled with hatred for the murder rate in Miami - in the 600s during 1981 - that they could not be bought off, although as the transporters said, a cop may not take a bribe of a $20, a $50, a $100 - but what about $100,000? "Everybody has a price," the movie sang, echoing Brasilia 18%. The difference is that here the prices are nominal - in Brasilia, they were "real" prices - the price of your family honor, the price of a human life.

Sometimes I wonder about the relationship between fiction and money. We've created a very swollen and bumbling dream called Capitalism, and in this dream we're able to reap the benefits of our hard work, and we're able to earn more, and anyone who can't keep up is necessarily evil. There's actually several fictions going on in these movies. There's the fiction of an accountable government and law enforcement (Jon's ex-girlfriend said, "What I want to know is, where'd the money go?" Then she raised her eyebrows as an explosion sounded, and we knew - financing Manuel Noriega, financing the Contras - and the entire theater seemed to cower in embarrassment for our own government); the fiction of the perpetrators, that as President Soeharto said, "what you call corruption, we call family values", that everything done was justified, that, "well at least I wouldn't kill the kids"; and the fiction of the victims, of Eugenia refusing to cook the books and thinking she would live to work another day, of coming to America to make a good, decent, honest living - the fiction of hope.

The fiction that we live in a world above money politics. Ugh. As the doomed boyfriend/filmmaker in Brasilia 18% rants, money squawks louder above anything else. And while we sleep in our cocaine or money-induced dreams, what happens? People die on the streets - people who happened to be standing outside a restaurant whose owner had pissed off the Cocaine Godmother, people who were unfortunate enough to be driving around a marked man in a taxi cab - people die in our drug-financed wars. Maybe it's time to follow Fiona Apple's example: "I got my feet on the ground and I don't go to sleep to dream".

And meanwhile here we sit in our dorm room listening to "Fiction (Dreams in Digital)" by Orgy:

She's lost in a coma where it's beautiful/ intoxicated from the deep sleep, deep sleep/ do you wonder what it's like living in a permanent imagination?/ sleeping to escape reality, but you like it like that/ guilty by design she's nothing more than fiction./ she dreams in digital, 'cause it's better than nothing./ now that control is gone, it seems unreal, she's dreaming in digital. she dreams in digital/ And your pixel army can't save you now, my finger's on the kill switch/ I remember I used to compose your dreams, control your dreams/ and don't be afraid to expose yourself before I shut you down/ you made some changes since the virus caught you sleeping...

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

That's Mr. Kaneda to you, punk!

Everyone, just... pretend to be normal.

You will suffer me.

Lots of respectable people have been hit by trains!

No, I am merely stating that uh... life finds a way.

Gee, I wish we had one of them doomsday machines.

when the wind is southerly, i know a hawk from a handsaw

About Me

The Creatrix

What's Happenin'

Straight to Hell

Brain Stew

The Speed of Sound

Whatever Gets You Through Today

I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For

Akira

That's Mr. Kaneda to you, punk!

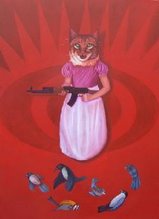

Kitty With A Tommy Gun

What's That Smell in the Kitchen? - Marge Piercy

All over America women are burning dinners. It's lambchops in Peoria; it's haddock in Providence; it's steak in Chicago tofu delight in Big Sur; red rice and beans in Dallas. All over America women are burning food they're supposed to bring with calico smile on platters glittering like wax. Anger sputters in her brainpan, confined but spewing out missiles of hot fat. Carbonized despair presses like a clinker from a barbecue against the back of her eyes. If she wants to grill anything, it's her husband spitted over a slow fire. If she wants to serve him anything it's a dead rat with a bomb in its belly ticking like the heart of an insomniac. Her life is cooked and digested, nothing but leftovers in Tupperware. Look, she says, once I was roast duck on your platter with parsley but now I am Spam. Burning dinner is not incompetence but war.

Little Miss Sunshine

Everyone, just... pretend to be normal.

Lord of the Rings

You will suffer me.

Poetry

Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening - Robert Frost

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village, though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound's the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark, and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

O Brother Where Art Thou

Lots of respectable people have been hit by trains!

Jurassic Park

No, I am merely stating that uh... life finds a way.

Emily The Strange

Dr. Strangelove

Gee, I wish we had one of them doomsday machines.

Scheherazade

Don't Panic, Little Stargazer belongs to sri angry angel.

: love love is a verb love is a doing verb : so fragile yet so devious : disdainful and curious : give me life give me pain give me my self again : i'm a firestarter twisted firestarter i'm the bitch you hated filth infatuated yeah : love of colors sounds and words is it a blessing or a curse : are you a part of the cure or are you part of the disease : i fought the war i fought the war i fought the war but the war won : wake up and face me don't play dead cuz maybe someday i will walk away and say you fucking disappoint me : you don't have to love me you don't even have to like me but you will respect me : don't let the walls cave in on you : sleeping in is giving in no matter what the time is : over there stands my angry angel and he's frowning like hell but i'm not feeling guilty :